The Final Frontier

March 30, 2014

Not your average nineteenth-century American landscape, is it?

Where are the soaring peaks, the thick foliage, the waterfalls? The ominous clouds representing the potential threat of American hubris? The tiny wagon trains and mountain men showing that few people were actually concerned about national hubris?

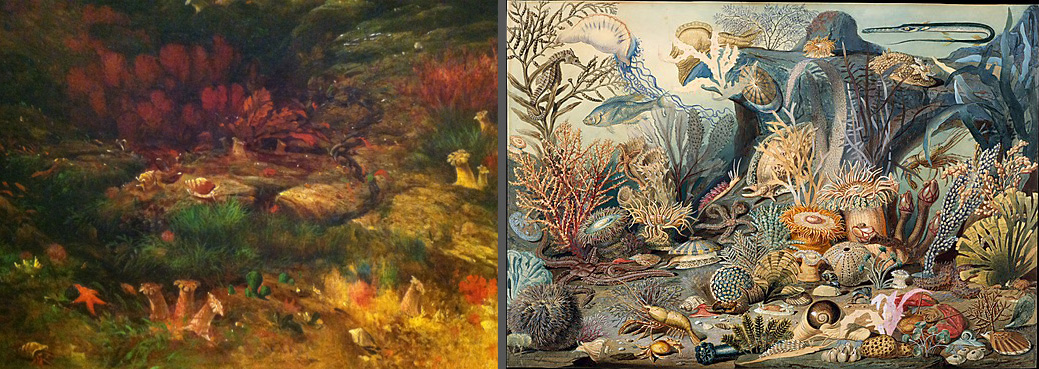

In truth, that’s all more or less there. But before I get to that, let’s just marvel at how weird this work of art is. There are many landscapes in the history of painting, and there are many marine paintings—lots of them also painted by Edward Moran, who was essentially the J.M.W. Turner of the United States. Stormy seas, wrecks, tall ships, you get the idea. But nowhere else in the nineteenth century does one find an underwater landscape painting. That is, unless you count Russian artist Ilya Repin’s Sadko in the Underwater Kingdom, which is more of a showcase for mermaid breasts than anything else (a friend of mine who is a scholar of Russian art calls it a “weird failure of a painting,” but I find the colors and patterns kind of charming).

This month I’m looking at The Valley in the Sea to celebrate my move back to Indianapolis. I realize these two things are incongruous (middle America = the bottom of the sea?), but Moran’s painting has always been one of my favorites in the Indianapolis Museum of Art’s collection. What is most intriguing about it is how it would have meant something vastly different to a viewer from the 1860s than it does to viewers today. When I was a kid, The Valley in the Sea certainly seemed fantastical, with its implication (to a seven-year-old, mind you) of the artist taking his paint box and easel down to the ocean floor and dabbing at his oversized canvas in a scuba suit. But the scene itself—the coral, rocks, snails, and anemone—was very, very familiar. I had seen it countless times in nature documentaries and, frankly, The Little Mermaid.

For the 1860s viewer, looking at this would be akin to us looking at a painting of the surface of Mars. In 1857, Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury wrote that for his predecessors in marine science, “the depths of the sea still remained as fathomless and as mysterious as the firmament above.” The depths of the deep, open ocean might as well have been outer space. No one knew how deep the ocean could get, or if there was a Kraken down there. For most people, it was a dark, mysterious place into which ships sank and out of which the fish they ate came. It was terrifying, and it was also the new frontier of exploration. In the next decade, Jules Verne sent his science-fiction heroes not just to the moon (From the Earth to the Moon, 1865), but beneath the surface of the world’s oceans (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, 1869).

James M. Sommerville printed by Christian Schussele, Ocean Life. Watercolor, gouache, graphite, and gum Arabic on off-white wove paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Erving Wolf, in memory of Diane R. Wolf, 1977.181.

Like Verne’s novels, Moran’s painting extrapolates on the latest science. Jacques Cousteau described it in 1971 as “a work of imagination, based on serious documentation.” The documentation was probably Maury’s The Physical Geography of the Sea (1857) and Dr. James M. Sommerville’s Ocean Life (1859), which featured illustrations like the one above. Sommerville, a pioneering marine biologist, was the painting’s first owner. At the time he bought the work, diving and submarine technologies were just inching into the modern era—to the benefit of marine science. No one had been to the deepest parts of the ocean, but newly-improved diving suits made glimpses of shallower areas much easier to manage. In this sense, The Valley in the Sea reminds me of many of Winslow Homer’s works, which (as curator Kathleen Foster has pointed out) feature cutting-edge rescue technologies that to viewers today may just look like a bunch of guys with boats.

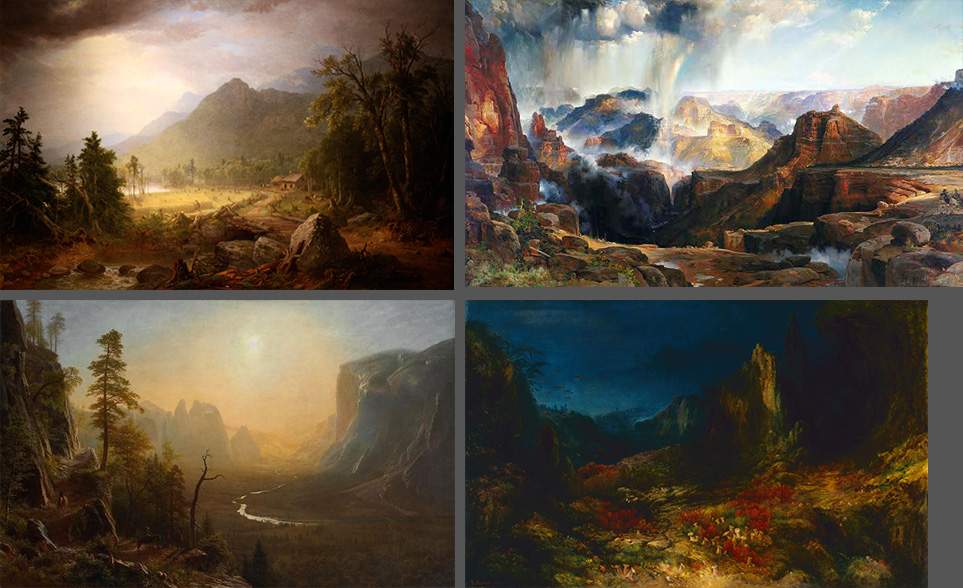

But, back to the landscape paintings. It’s probably no accident that The Valley in the Sea is stylistically and compositionally similar to contemporary depictions of the Western United States. In the early part of the century, the West was the terrifying new frontier of exploration, full of stunning geography and unknown challenges. By the 1860s, though, Lewis and Clark were long gone. Surveyors were still mapping the West, and painters traveled out in droves, but the U.S. government pretty much knew what was there. The West had already been “won,” so to speak, and whatever we may think of this now, European-Americans felt an ongoing responsibility to “tame” it. Since the sea was one of the next segments of the world on the United States’ long list of things to catalog and conquer, the West was Moran’s ideal model.

Thomas Moran, The Chasm of the Colorado. Oil on canvas mounted on aluminum, 1873-74. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Lent by the Department of the Interior Museum, L.1968.84.2.

Albert Bierstadt, Yosemite Valley, Glacier Point Trail. Oil on canvas, circa 1873. Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Mrs. Vincenzo Ardenghi, 1931.389.

Valley in the Sea.

Of course, nowadays we send not painters but robots to explore new frontiers, and like us, they take pictures of themselves: