Le Monocle

April 30, 2014

Most of us have one of those friends—dramatic and a little odd, with questionable aesthetic taste. Maybe they dye their hair orange or dress like Bellatrix Lestrange, or wear sandals with argyle socks in December. But most of us also wouldn’t change that person the least bit because they are fabulous.

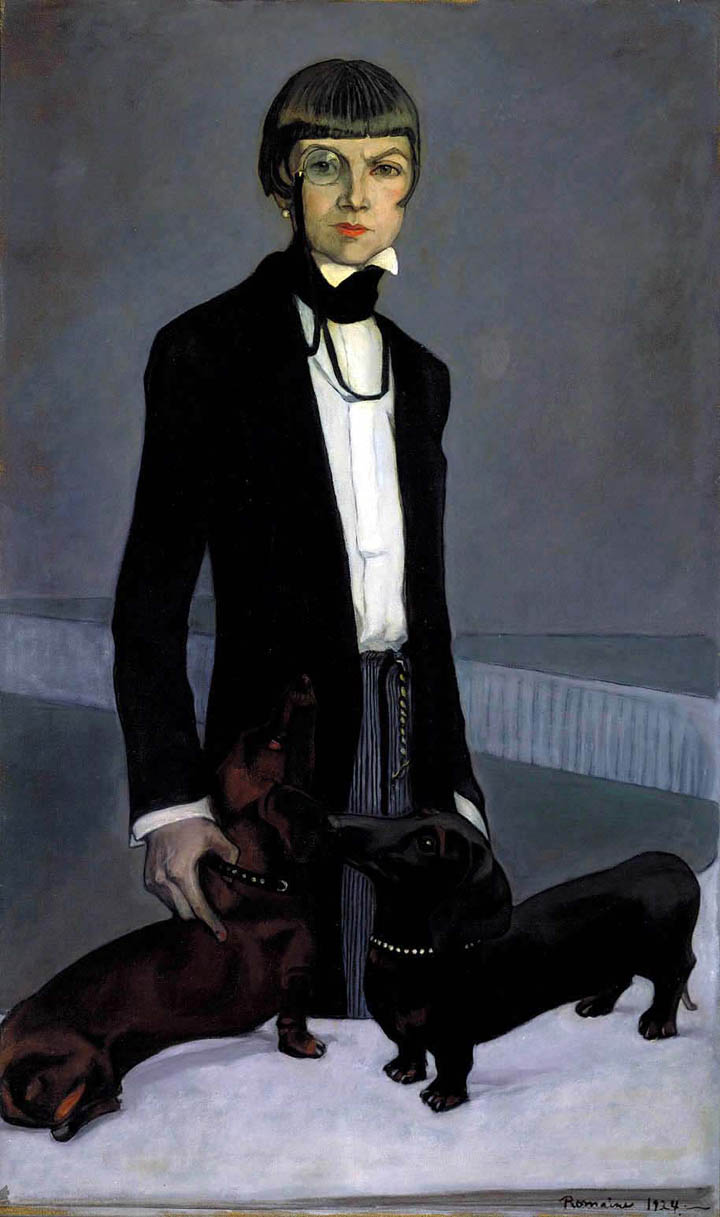

For expatriate American painter Romaine Brooks, Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge, was that person. In the midst of painting this portrait, Brooks wrote to her lover, the writer Natalie Barney: “Una is funny to paint. Her get-up is remarkable. She will live perhaps and cause future generations to smile.”

Brooks was independently wealthy and could paint whomever she chose, which usually meant women from Barney’s regular literary salons in Paris. Truman Capote described these gatherings as “the all-time ultimate gallery of all the famous dykes from 1880 to 1935 or thereabouts,” so Brooks had no shortage of people to paint. Usually her subjects are self-possessed, stylish, graceful, and androgynous. The titles accompanying them also suggest a flexible understanding of gender, as in her portrait of artist Gluck, titled Peter (A Young English Girl). BEST TITLE EVER.

Una was all these things, with a dash of ridiculous. Mostly this is due to the glaringly retro monocle and the pair of dachshunds atop the table in front of her. However, there are express reasons for their presence. Troubridge was not alone in her love of masculine clothing. Fashionable queer women in interwar Paris and London had begun donning suit jackets, pants, and cravats, each one challenging accepted notions of how women should look and be. Brooks herself had spurred the breakup of her own marriage by refusing her husband’s demand that she wear feminine clothing in public. It is hard to say how many of Brooks’ friends would today identify as trans, and not as women at all, but is worth considering, as is the intended message broadcast by an androgynous style. To the average person on the street, a woman in menswear would look eccentric, but might not be immediately assumed queer. To women who liked women, however, it would be obvious.

The same goes for the monocle. Le Monocle was the name of a popular Parisian lesbian bar, and sporting a monocle oneself was pretty much a dead giveaway. Other queer European women at the time, like German writer Sylvia von Harden, were depicted wearing them. However, it remains that most people—queer or not—still would have found it eccentric (I mean, it’s a monocle). The photographer Brassaï frequented the club, and not one of the subjects in his pictures is actually wearing a monocle.

Most of the suit-wearing patrons at Le Monocle seem to have embraced a modern style. The tailored suits, Windsor knots, and pocket squares they favored were popularized in the interwar period by the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII, later the Duke of Windsor) and other European aristocrats. Some of Brooks’ milieu, though, took things in a more…artistic direction, hearkening back to early Victorian dandies like Beau Brummel. This is where Una’s high collar and neck scarf come from (Is anyone else thinking of Mr. Darcy?). It’s easy to imagine the dandy’s appeal to women like Troubridge and Brooks. He was stylish and independent, and his attention to fashion and beauty rendered him vaguely androgynous in the public eye. Brooks ran in a fashionable crowd that had no shortage of vaguely androgynous modern dandies, male as well as female, and for a few weeks was even engaged to one: Lord Alfred Douglas, a.k.a. Oscar Wilde’s boyfriend (OMG).

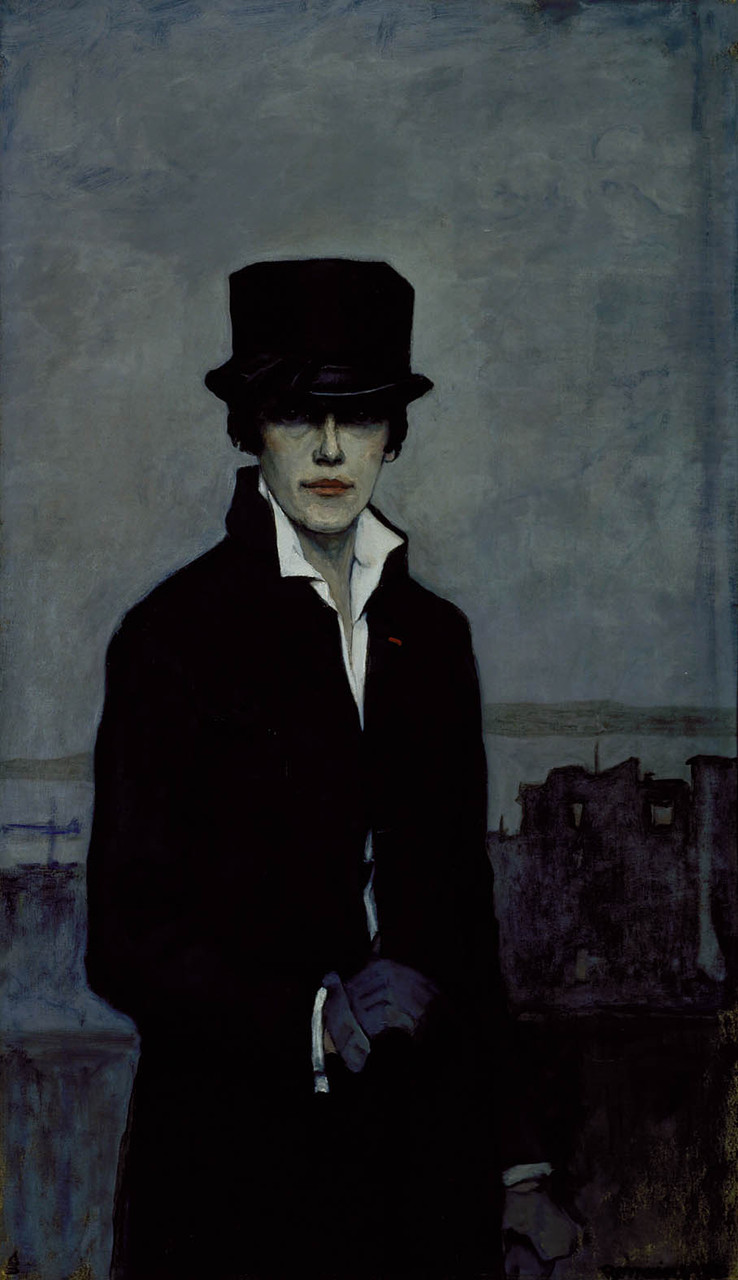

I feel like Brooks is judging me here a bit, don’t you? The shadow over her eyes is usually interpreted as a reference to her semi-masked sexuality, but I feel it also cements her position as an observer: the critic rather than the criticized. Brooks plays it cooler than Troubridge, with a top hat as her only nod to Victorian fashion. Top hats were thoroughly out of style in the 1930s, unless you were the Earl of Grantham, a posh banker, or a Hollywood showman. Or a lady on horseback. In this sense, Brooks’ style is athletic as well as dandyish. And despite her waxy sheen and deep black overcoat, it’s also a bit risqué. Her lips are a coral slash across a sea of gray, and not even Marlene Dietrich unbuttoned her shirt that far when she wore masculine clothing.

Troubridge, a sculptor and literary translator, was the most fabulous of all the women to meet Brooks’ critical eye. And I’ll add that she sure does meet it. The monocle perched beside her nose suggests careful study, and (literally and figuratively) it magnifies her arched brows and appraising stare. No, my sausage dogs are not silly, she seems to say. In fact, they were rather magnificent, as dachshunds go. These two were a prize-winning pair given to her by her longtime partner, the novelist Radclyffe Hall. Troubridge loved Hall dearly, and the dogs’ presence in the portrait (especially since they are a pair) provides a link to their relationship.

There are many stories I could tell about Troubridge, but I’ll end with the saddest one: Nineteen years later, Radclyffe Hall fell ill and died. Troubridge, in possession of all of Hall’s suits, had them recut to fit her, and wore them often.

She makes more sense with some context, doesn’t she?